The icon is painted in egg tempera with gold leaf on wood primed with gesso over cloth. The back is unpainted and has two horizontal battens. A brown painted band frames the icon while the reverse is covered with priming.

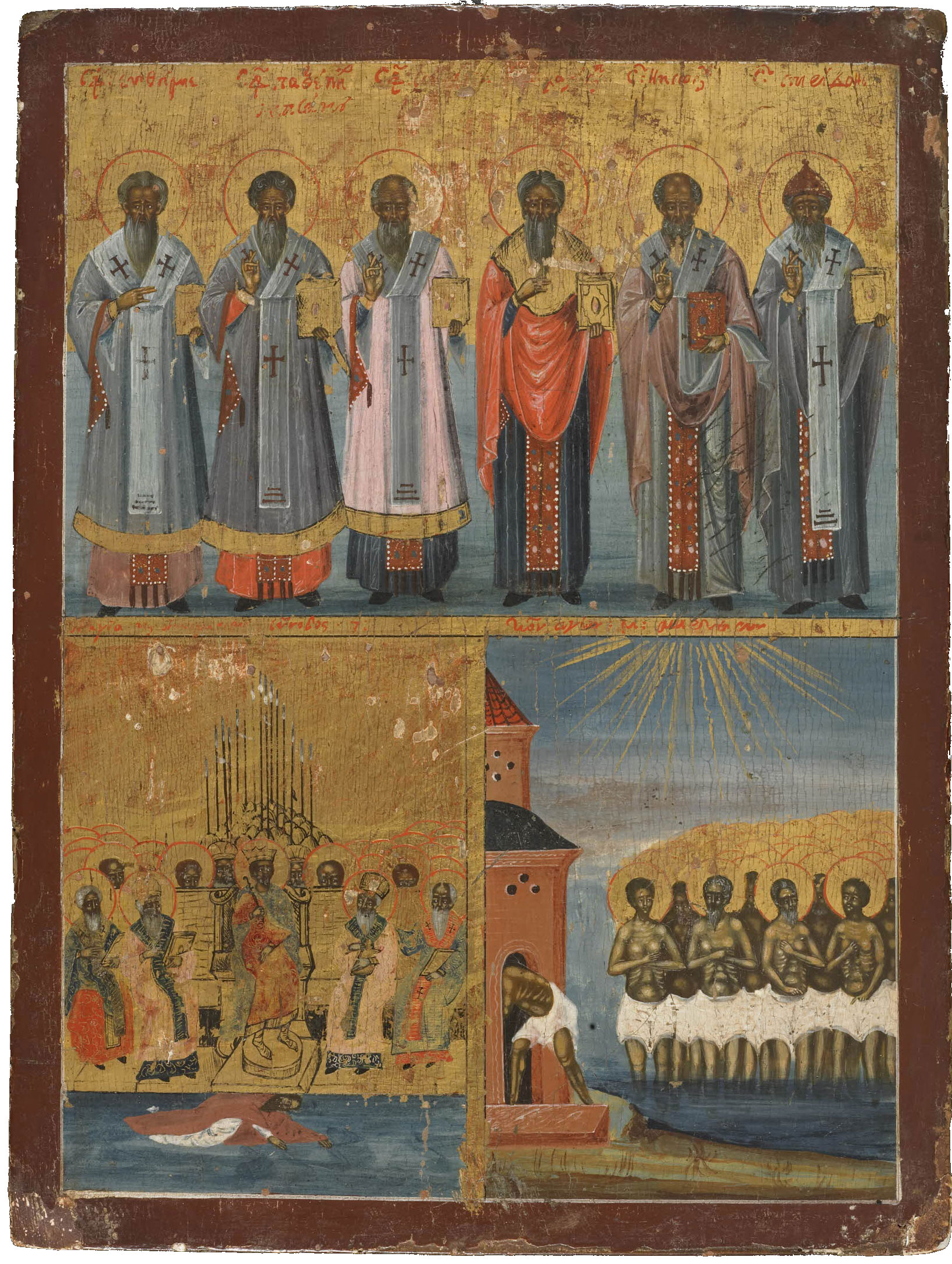

Three different scenes are represented in two registers. In the upper part, six standing saints are depicted with accompanying minuscule inscriptions in Cyrillic. Though the painted surface is quite worn and some letters are not fully preserved, one can still identify the majority of the saints. Moving from left to right, the inscriptions read: Сф. Еvθiмie (St Euthymios), Сф. Парθенiе [Лам]псак(скiи) (St Parthenios of Lampsakos), Сф. […] (St (unidentified); [Сф.] Ха[рала]мп(ie) (St Charalambos); С. Никола(е) (St Nicholas); С.Спирiдонь (St Spyridon). The lower register is divided into two parts: on the left is the First Ecumenical Council of Nicaea (325) identified in Greek minuscule as Η ΑΓΙΑ [..] ΟΙΚΟΥΜΕΝΙΚΗ CΥΝΟΔΟC (‘the Holy […] Ecumenical Synod’). On the right are the Forty Martyrs of Sebasteia also inscribed in Greek: ΤωΝ ΑΓΙωΝ Μ ΜΑΡΤΥΡωΝ (‘of the Holy Forty Martyrs’). The six saints stand frontally in similar positions, each supporting a Gospel book with their [his?] left hand and raising their [his?] right in blessing. They are dressed in the garments of bishops, apart from St Charalambos who is not depicted in the characteristic omophorion (a long scarf with crosses). This is due to the fact that it is not certain whether he was a bishop or a priest of Magnesia, Asia Minor. All five bishops are wearing the sticharion (a long tunic), a dark red epitrachelion ending with tassels, an omophorion and the epigonation in the shape of a rhombus. Yet, there is some variation in their vestments. The three figures on the left are portrayed in a sakkos (similar to a dalmatic), usually worn by Patriarchs and some high-ranking bishops, while the two bishops on the right, as well as St Charalambos, are in a phelonion (sleeveless mantle).

In the scene of the First Ecumenical Council (325), Constantine the Great in luxurious red and pale blue garments is seated on a throne presiding over the Church Fathers. Only those sitting in the front row are fully visible; the rest are only indicated by their heads and haloes. A group of guards forming a pyramid with their helmets and spears are shown behind the emperor, while before him is the fallen figure of Arius who was condemned for heresy.

The Forty Martyrs of Sebasteia are shown standing on a frozen lake, condemned by the Roman Emperor Licinius for refusing to renounce Christianity. They are seen in the process of being frozen to death, except for the one who enters the warm bathhouse.

In 2014, Robin Cormack and Maria Vassilaki examined the icon and its inscriptions and deduced that the attribution when the icon entered the British Museum in 1994 as Greek was incorrect, since the script of the inscriptions was Cyrillic and not Greek. However, it remained likely that the artist may have had Greek models in front of him, and was copying them. The investigation of Eleni Dimitriadou was generously assisted by the examination of the inscriptions by Dr Georgi Parpulov, who contributed the opinion that the Cyrillic inscriptions were in Romanian. Others however were in Greek.

Icons with various compositions arranged in two registers are not unusual and many of them include rows of standing saints, such as the 15th-century panel from the Monastery of Xenophon, Mount Athos (Kyriakoudis et al. 1998) and the 1800 icon from the Church of St Paraskevi, in Prëmet, now housed in the National Museum of Medieval Art, Korcë, Albania (Tourta 2006). In the lower left Church Council scene, the arrangement of the seated figures side by side in a straight line, as well as the presence of a group of guards, diverge from the Byzantine tradition, where in council scenes the Church Fathers are shown in a semicircle and no soldiers are portrayed (Walter 1970, figs 7, 33). Portable icons of the subject are relatively rare and postdate 1453 (Walter 1991–2), the earliest of them being that by Michael Damaskenos dated in 1591, part of the Collection of Ecclesiastical Art, St Catherine of the Sinaites, Herakleion, Crete (Borboudakis 1993). The presence of a sizeable group of soldiers holding long weapons, as in the BM panel, finds parallels in works from the region of Wallachia and Moldavia (Drăgut 1983). Among the closest examples are the 16th-century fresco of the Council of Ephesus (431) from the Cathedral of St Paraschiva in the city of Roman (Sabados 1990) and the fresco of the Second Council of Constantinople (553) from the Holy Trinity Church in Cozia, dating from 1386 but repainted in the 16th and 17th centuries (Walter 1970, 97–8, fig. 50). In both works the emperor is in the middle of a line of seated Church Fathers while the guards behind him form a pyramid. This scheme is in use until the 19th century as seen in the drawings of the painter Radu, whose last sketch dates to 1803 (Dumitrescu and Voinescu 1974).

On the lower right, the scene of the Forty Martyrs closely follows an iconography employed in icons from northern Greece drawing on 16th-century Cretan painting, such as that from the collection of the Museum of Byzantine Culture, Thessaloniki, dated to the 17th century (Staikos 2008). In this icon the martyrs form a group on the right side while on the left is a bathhouse where one of them, Dadianos, escapes the ice. The BM icon differs from the Thessaloniki panel in that rays of light have replaced the figure of the blessing Christ portrayed at the top centre of the scene and there are no crowns hovering above the Martyrs. Throughout the icon the flesh parts of the figures are modelled with dark brown, ochre and some white lights on the forehead and hands. The garments are rendered in a naturalistic way, though not very successfully. This dry and linear style is encountered in works from the Balkans dating to the 18th century. The existence of inscriptions in both Cyrillic and Greek points to the proposal that the icon was made during the 18th and early 19th centuries when the Greek Phanariote families achieved positions of considerable power in the Ottoman administration of Moldavia and Wallachia.

The relatively small size of the icon suggests that it may have been designed for private prayer. A possible explanation for the choice of these varying subjects is the creation of a panel that emphasised the Christian Creed, as formulated during the First Ecumenical Council of Nicaea. St Nicholas and St Spyridon participated in this Council and St Euthymios (Bishop of Sardis) was involved in the Second Council of Nicaea (787) that repudiated iconoclasm and restored the veneration of icons. St Parthenios, under the auspices of Constantine the Great, spread the Christian faith in the see of Lampsakos, while St Charalambos and the Forty Martyrs of Sebasteia were among the earliest who suffered death for their faith in Christ. Therefore, the BM icon communicated the importance of the true Creed and the refutation of heresy while the saintly figures represented on it would serve as paradigms of faith to the faithful.

It can be seen that the icon painter has used an incised design to outline the figures and decorate their garments, suggesting the employment of pricked drawings or cartoons from the Greek world

Literature: C. Walter, L’iconographie des conciles dans la tradition Byzantine, Paris, 1970; F. Dumitrescu and T. Voinescu, Pagini de veche artă românească III, Bucharest, 1974, 155, 158, 213, no. 161, fig. 6; V. Drăgut, Die Wandmalerei in der Moldau, Bucharest, 1983, pl. 215; E. Kyriakoudis et al, Ιερά Μονή Ξενοφώντος. Εικόνες, Mount Athos, 1998, 87; C. Walter, ‘Icons of the First Council of Nicaea’, Δελτίον της Χριστιανικής Αρχαιολογικὴς Εταιρείας 16 (1991–2), 209–18, at 209; M. I. Sabados, The Diocesan Cathedral of Roman, Huși, 1990, 52, fig. 154; M. Borboudakis (ed.), Εικόνες της κρητικής τέχνης. Από το Χάνδακα ως τη Μόσχα και την Αγία Πετρούπολη (exh. cat., Basilica of St Mark – Church of St Catherine), Herakleion, 1993, 459–61, no. 101; A. Tourta (ed.), Icons from the Orthodox Communities of Albania. Collection of the National Museum of Medieval Art, Korcë, Thessaloniki, 2006, 178–81, no. 61; K.S. Staikos (ed.), From the Incarnation of Logos to the Theosis of Man. Byzantine and post-Byzantine Icons from Greece (exh. cat., Byzantine and Christian Museum), Athens, 2008, 90, no. 40; R. Cormack, Icons, London, 2007 (repr. 2014), no. 25, 119.

Eleni Dimitriadou